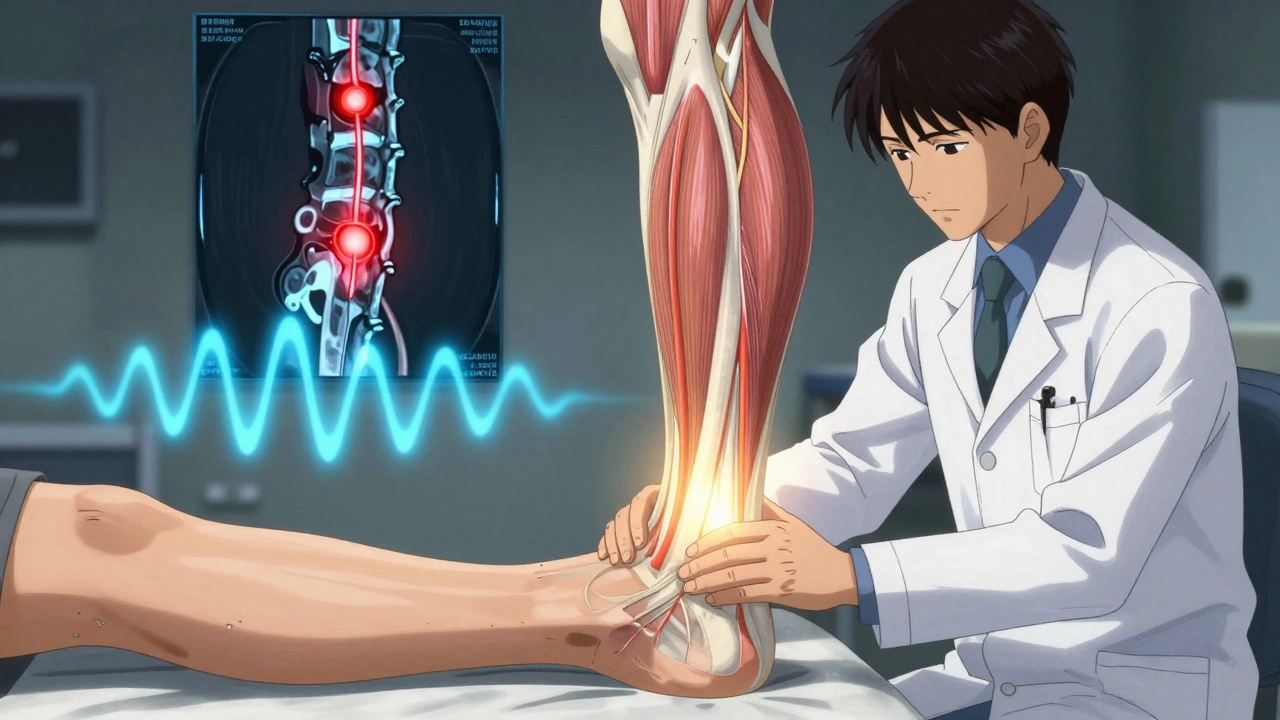

When you start noticing your legs feel heavy after walking just a few blocks-like they’re filled with wet sand-and you have to stop, bend forward, or lean on a shopping cart to make it go away, it’s not just getting older. It could be neurogenic claudication, the most common symptom of lumbar spinal stenosis. This isn’t a muscle cramp or poor circulation. It’s your nerves being squeezed in your lower spine, and if you don’t recognize the signs, you might end up chasing the wrong treatment for months-or years.

What Neurogenic Claudication Really Feels Like

People describe it in different ways: ‘like my legs are turning to lead,’ ‘my toes go numb halfway down the block,’ or ‘I can’t walk past the mailbox without sitting down.’ But there’s a pattern. The pain doesn’t come from standing still. It shows up when you’re moving-walking, standing for too long-and it gets worse the longer you keep going. Then, suddenly, it stops. Not because you rested. Because you bent forward.

That’s the key. If you sit down, lean on a cane, or push a shopping cart, the pain fades within seconds. This is called the ‘shopping cart sign,’ and it’s seen in 68% to 85% of people with true neurogenic claudication. It’s not random. When you bend forward, your spinal canal opens up a little. That takes pressure off the compressed nerves. Your body finds the only position that gives relief-and it’s not lying down or resting like with vascular issues.

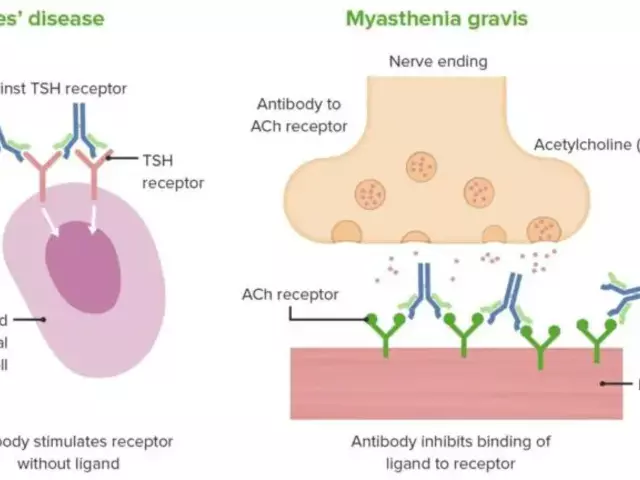

Unlike vascular claudication-where poor blood flow causes leg pain that eases with rest-neurogenic claudication needs forward flexion. You might have strong pulses in your feet, normal skin color, and no swelling, but still be in pain. That’s because it’s not your arteries. It’s your nerves. A simple test: if you can walk 200 feet with pain, but walk the whole grocery store while leaning on a cart, that’s neurogenic claudication.

Why Most People Get It Wrong

Doctors often mistake this for heart or artery problems. Why? Because ‘claudication’ sounds like a vascular term. Many patients see three or four doctors before someone asks, ‘Do you feel better when you bend forward?’ One patient on Healthgrades wrote: ‘It took three doctors before someone realized it wasn’t vascular-my pulses were always strong, but no one asked if bending helped.’

That’s the problem. Vascular claudication comes from blocked arteries. Treatment? Blood thinners, angioplasty, stents. Neurogenic claudication? None of that helps. You need to relieve pressure on the nerves. Misdiagnosis leads to unnecessary tests, wrong medications, and wasted time. The Royal Spine Surgery team says most patients find early relief just by leaning forward-so if your doctor doesn’t ask about posture, they’re missing the diagnosis.

There’s another clue: weakness in the muscles of your feet. Specifically, wasting of the extensor digitorum brevis-a small muscle under your foot. It’s not something you can feel yourself, but a trained clinician can spot it during a quick exam. It’s a reliable sign of long-term nerve compression.

How Doctors Diagnose It (And Why Imaging Alone Isn’t Enough)

You might think an MRI is the answer. But here’s the twist: up to 67% of people over 60 have spinal narrowing on an MRI-and no symptoms at all. That means your scan might show stenosis, but if you don’t have the right symptoms, you don’t have neurogenic claudication. Diagnosis isn’t about the image. It’s about the story.

Doctors look for four key things:

- Leg or buttock pain that starts while walking or standing

- Pain that gets better when you sit or bend forward

- Relief when using a walker or shopping cart

- Normal foot pulses and no signs of poor circulation

They’ll also check your spine’s range of motion. If bending backward hurts but bending forward feels better, that’s a red flag. They might do the five-repetition sit-to-stand test. If you can do it in under 10 seconds, your function is still decent. If it takes 20 seconds or more, you’re likely in the moderate to severe range.

Imaging-MRI or CT-comes after the story makes sense. It’s not to confirm the diagnosis. It’s to plan treatment. Is the narrowing at one level? Two? Is it central or on the sides? That tells the surgeon what kind of procedure you might need.

First-Line Treatment: Don’t Rush to Surgery

Most people don’t need surgery. In fact, 82% of patients with early-stage neurogenic claudication see real improvement with conservative care. The first step is simple: move smarter.

Physical therapy focuses on flexion-based exercises. That means movements that bend your spine forward-knees-to-chest stretches, pelvic tilts, seated forward bends. You’ll also learn posture training: how to walk with a slight forward lean, how to sit without slumping, how to use a walker or cane properly. It’s not about strengthening your back. It’s about protecting your nerves.

Exercise matters too. Walking is still good-but not straight. Walk in short bursts. Stop. Lean. Walk again. Many patients find they can double their distance by using this ‘stop-and-bend’ method. A 2023 study from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons found structured exercise programs improved walking ability more than medication alone.

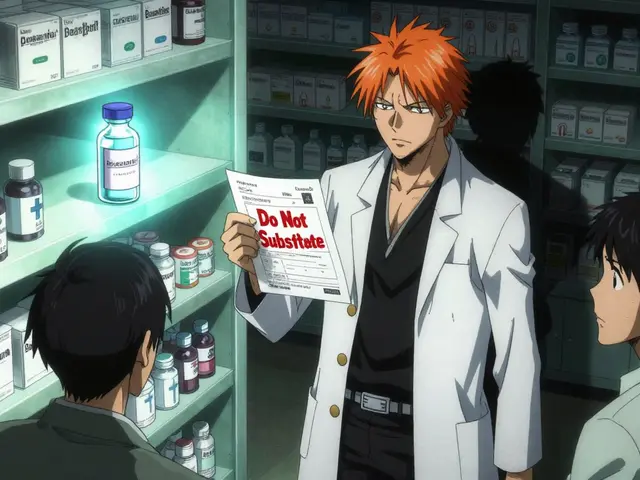

Pain relief? Over-the-counter NSAIDs like ibuprofen help for flare-ups. But they don’t fix the root problem. Some doctors try epidural steroid injections. They work for about half to 70% of people-but only for a few months. It’s not a cure. It’s a bridge.

When Surgery Becomes Necessary

If you’ve tried 3 to 6 months of physical therapy, posture changes, and pain management-and you’re still in pain, losing strength, or having trouble with daily tasks-it’s time to talk surgery.

The goal? Take pressure off the nerves. The most common procedure is a laminectomy-removing part of the bone that’s squeezing the spinal canal. For some, a laminotomy (partial removal) or minimally invasive decompression is enough. A newer option, the Superion device, is an implant that holds the spine in a slightly flexed position, keeping the canal open. Approved by the FDA in early 2023, it’s shown 78% patient satisfaction after two years.

Success rates? Studies show 70% to 80% of well-selected patients get ‘good to excellent’ results one year after surgery. But surgery isn’t magic. It doesn’t reverse nerve damage. If you’ve had weakness or numbness for years, some symptoms may stay. The goal is to stop it from getting worse and give you back your mobility.

What to Expect After Surgery

Recovery isn’t overnight. Most people go home the same day or after one night. You’ll need to avoid bending backward for weeks. Walking is encouraged-but again, with a forward lean. Physical therapy resumes, focusing on core stability and safe movement patterns. Most patients return to normal walking within 6 to 12 weeks.

But the real win? Getting back to the things you love. Walking the dog. Shopping without stopping. Playing with grandkids. One patient from Florida said: ‘I used to wait for my wife to finish the grocery run so I could sit in the car. Now I walk the whole store. I didn’t think I’d ever get that back.’

The Bigger Picture: Why This Is Getting More Common

Spinal stenosis isn’t rare. About 200,000 Americans are diagnosed each year. And it’s only going up. The global population over 65 will nearly double by 2050. As we age, discs flatten, ligaments thicken, bones grow extra spurs-natural wear and tear that narrows the space for nerves. That’s why neurogenic claudication is no longer just a ‘elderly problem.’ It’s a growing public health issue.

Minimally invasive surgeries are rising fast. Between 2018 and 2022, their use jumped 35%. That’s good news. Less tissue damage, shorter recovery, fewer complications. But the real progress? Better awareness. More doctors are learning to ask the right questions. More patients are learning to recognize the ‘shopping cart sign’ before it’s too late.

The future? A standardized diagnostic tool is in development by the International Spine Study Group. Expected in late 2024, it will help doctors combine symptoms, exam findings, and imaging into one clear decision path. No more guessing. Just clear answers.

Final Thoughts: Know Your Body

If your legs hurt when you walk-but bend forward and it disappears-you’re not imagining it. You’re not just getting old. You might have neurogenic claudication. And if you do, you have options. You don’t need to give up walking. You don’t need to live with pain. You just need to know what you’re dealing with.

Start by tracking your symptoms. How far can you walk before pain hits? Do you lean forward to relieve it? Do you use a cart or walker? Write it down. Take it to your doctor. Ask: ‘Could this be spinal stenosis?’ Don’t let them dismiss it as ‘just arthritis.’

Neurogenic claudication isn’t a death sentence. It’s a signal. And with the right diagnosis and approach, you can still walk-without stopping.

Is neurogenic claudication the same as vascular claudication?

No. Neurogenic claudication is caused by nerve compression in the spine, usually from spinal stenosis. Pain comes with walking or standing and improves when you bend forward or sit. Vascular claudication is caused by poor blood flow from blocked arteries. Pain comes with walking but improves with rest-even if you’re standing still. You can have strong pulses and still have neurogenic claudication. The treatments are completely different.

Can I still walk if I have neurogenic claudication?

Yes, and you should. Walking helps maintain mobility and nerve function. But you need to adjust how you do it. Walk in short bursts. Stop and lean forward when pain hits. Use a walker or shopping cart to support your spine. Many people double or triple their walking distance by using this technique. Avoid long, straight walks without breaks.

Do I need an MRI to diagnose neurogenic claudication?

Not necessarily. Diagnosis is based on your symptoms and physical exam. Many people have spinal narrowing on MRI with no pain at all. An MRI is used to confirm the cause and plan treatment-not to make the diagnosis. If your history and exam strongly point to neurogenic claudication, you can start conservative treatment without imaging.

How long does physical therapy take to help?

Most people need 6 to 8 weeks of consistent therapy to see real improvement. It’s not about quick fixes. It’s about retraining your posture, movement patterns, and muscle use. If you stop early, you won’t get the benefit. Stick with it-even if you don’t feel better right away. Progress is slow but steady.

What happens if I ignore neurogenic claudication?

It won’t go away on its own. Over time, nerve compression can lead to permanent weakness, numbness, or loss of balance. You may start falling more, lose muscle in your legs, or have trouble controlling your bladder or bowels in severe cases. The longer you wait, the harder it is to recover-even with surgery. Early action gives you the best chance to keep your mobility.

For most people, neurogenic claudication isn’t a crisis-it’s a cue. A signal to pay attention, adjust, and act. You don’t have to stop living. You just need to walk smarter.

Audrey Crothers

December 12, 2025 AT 02:29OMG I literally thought I was just getting old 😭 I used to walk my dog 2 miles, now I can’t make it to the mailbox without leaning on my cart. When my PT asked if bending forward helped, I was like... wait, WHAT? That’s not normal?? Turned out I had stenosis. This post? Saved my life. 🙏

Stacy Foster

December 13, 2025 AT 15:02They don’t want you to know this-but spinal stenosis is a pharmaceutical scam. The real cause? EMF radiation from 5G towers weakening your spinal discs. They push surgery because implants are profitable. Your ‘shopping cart sign’? A distraction. Look at the FDA’s hidden studies. They’ve been suppressing the truth since 2019. 🤫

sandeep sanigarapu

December 15, 2025 AT 01:46Thank you for sharing this clear and accurate information. In India, many elderly patients are misdiagnosed with arthritis. The concept of forward flexion relief is rarely discussed by local physicians. This knowledge could prevent years of unnecessary suffering.

Nathan Fatal

December 16, 2025 AT 23:40What’s fascinating is how the body self-diagnoses. We don’t need doctors to tell us what’s wrong-we just need to listen. The shopping cart isn’t just a tool, it’s a survival mechanism. Your spine is screaming, ‘I need space.’ And you, by bending, become your own surgeon. That’s biology as poetry.

wendy b

December 18, 2025 AT 09:49Actually, I think you're oversimplifying. Neurogenic claudication is a subset of degenerative lumbar pathology, and the 'shopping cart sign' is only reliable in conjunction with neurodynamic testing and segmental mobility assessment. I mean, come on-how many people even know what the extensor digitorum brevis is? You need more nuance.

Rob Purvis

December 19, 2025 AT 17:39Wait-so if you have strong pulses, no swelling, and pain only when upright-but it vanishes when you lean forward-it’s NOT vascular? That’s wild. I had a cousin who got stents for ‘claudication’ for two years before someone asked him if he leaned on his cane. He cried. Like, full-on ugly crying. This is why we need better training.

Laura Weemering

December 21, 2025 AT 13:05It’s all so tragic, isn’t it? We’re literally being crushed by time-our spines, our dignity, our autonomy. The system doesn’t care. They’ll give you ibuprofen and call it a day. Meanwhile, your nerves are slowly dying, and you’re told to ‘just walk it off.’ I’m not even sure I want to be fixed anymore…

Reshma Sinha

December 23, 2025 AT 02:19Just started PT last week-knees-to-chest, pelvic tilts, walking with a cane-and already I’m going farther! It’s not magic, but it’s real. If you’re reading this and hesitating-just try it. One minute a day. You’ve got nothing to lose but the pain. 💪❤️

Lawrence Armstrong

December 24, 2025 AT 11:30My dad had this. Didn’t know what it was until he started using a walker. He said, ‘It’s like my legs are stuck in molasses.’ We got him the Superion device last year. He’s walking the mall again. No surgery. No opioids. Just a little titanium spacer. 🤖❤️