Vancomycin Infusion Rate Calculator

Safe Infusion Calculator

Calculate if your vancomycin infusion rate is safe to prevent flushing syndrome.

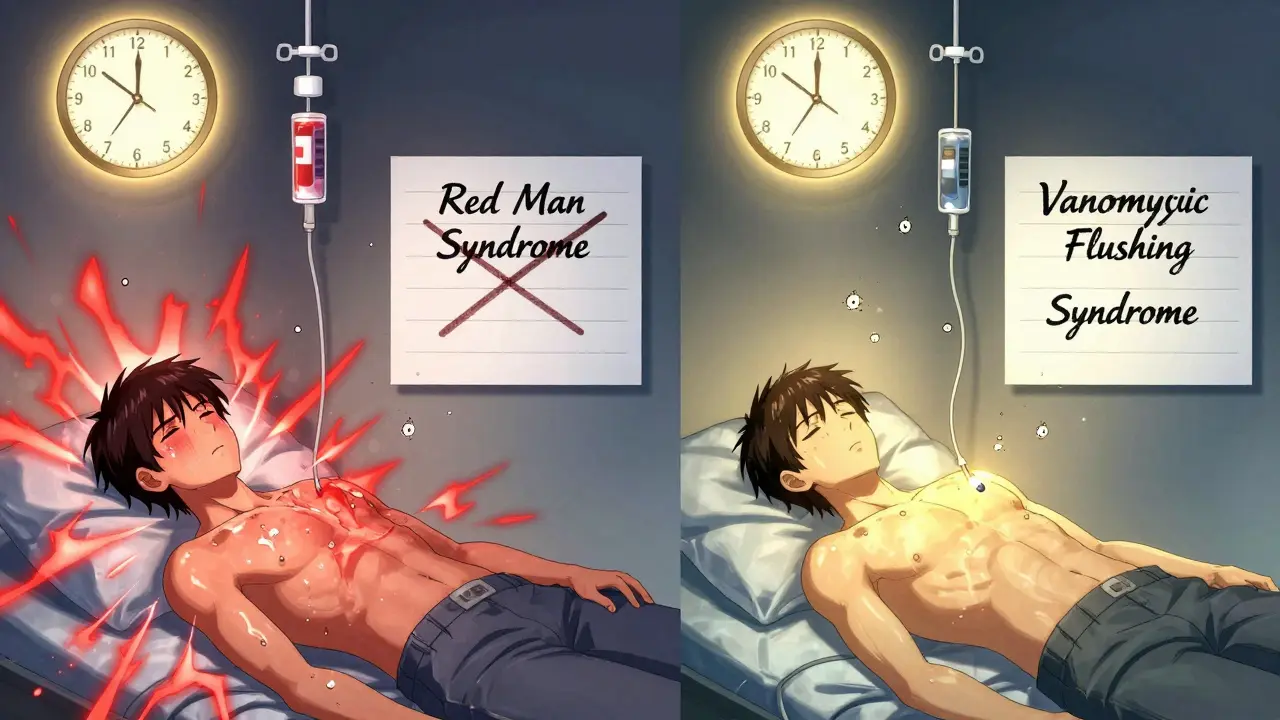

Vancomycin is a powerful antibiotic used to treat serious bacterial infections like MRSA and Clostridioides difficile. But if it’s given too fast, it can trigger a reaction that looks scary - flushing, itching, red skin, even low blood pressure. For years, this was called red man syndrome. That name is outdated, offensive, and medically inaccurate. Today, doctors call it vancomycin infusion reaction or vancomycin flushing syndrome. And here’s the good news: it’s almost always preventable.

What Actually Happens During a Vancomycin Infusion Reaction?

This isn’t an allergy. It doesn’t involve your immune system remembering the drug from a past dose. Instead, vancomycin directly triggers mast cells and basophils - the same cells that release histamine during allergic reactions - to dump histamine into your bloodstream. That histamine causes blood vessels to widen, skin to flush, and nerves to send itch signals.

The reaction usually starts 15 to 45 minutes after you begin the infusion. You might feel warmth spreading across your face, neck, and chest. Your skin turns red or pink. Itching follows. In more intense cases, your heart races, your blood pressure drops, or you feel tightness in your chest or back. Muscle spasms and trouble breathing can happen too, but true airway swelling - like with anaphylaxis - is rare.

Studies show this isn’t random. In one classic 1988 study, 9 out of 11 healthy adults got a reaction after receiving 1,000 mg of vancomycin over just one hour. None of them reacted when the same dose was given slowly over more than two hours. The faster the infusion, the worse the reaction. Infusing at more than 10 mg per minute is the main trigger.

Why the Name Changed - And Why It Matters

“Red man syndrome” was never a scientific term. It was a crude, visual label that reduced a medical event to a stereotype. In 2021, a study in Hospital Pediatrics found that over 60% of electronic health records still used this outdated phrase. That meant patients were wrongly labeled as “allergic” to vancomycin - a label that could block them from getting the best treatment later.

One hospital system replaced every instance of “red man syndrome” with “vancomycin flushing syndrome” in their records. Within three months, the use of the old term dropped by 17%. That’s not just semantics. It’s patient safety. When a patient is incorrectly labeled as “allergic,” doctors avoid vancomycin and reach for broader-spectrum antibiotics. That increases the risk of resistance, side effects, and longer hospital stays.

Major institutions like UCSF and the Infectious Diseases Society of America now require the term “vancomycin infusion reaction” in all clinical documentation. The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology supports this change as part of removing racist and biased language from medicine.

How to Tell It Apart From a Real Allergy

Not all skin reactions to vancomycin are the same. A true IgE-mediated allergic reaction - like anaphylaxis - is rare. In a study of 198 patients with reported vancomycin “allergies,” only 3% had true anaphylaxis. Another 4% had severe skin reactions like DRESS, SJS, or TEN - these are life-threatening and need immediate care.

Vancomycin infusion reaction is different. It happens during the first dose. It doesn’t cause swelling of the tongue or throat. It doesn’t trigger wheezing or collapse. It’s tied to infusion speed. And it gets better with time - many patients have milder reactions on repeat doses, a sign the body is adapting.

If you’ve had a reaction before, don’t assume it’s an allergy. Talk to your doctor. They can test for true IgE involvement or refer you to an allergist. Mislabeling yourself as allergic to vancomycin could mean you’re denied the most effective antibiotic for a life-threatening infection.

How to Prevent It - The Simple Rules

The best treatment? Slow down the drip.

Administering vancomycin at a rate of 10 mg per minute or slower prevents almost all cases. That means a 1-gram dose should take at least 100 minutes to infuse. Many hospitals now use infusion pumps programmed to deliver vancomycin over 60 to 120 minutes as a standard practice.

Don’t rush it. Don’t piggyback it with other IV fluids unless necessary. Avoid giving it at the same time as other drugs that can trigger histamine release - like opioids, muscle relaxants, or contrast dye used in CT scans.

Pre-medication with antihistamines (like diphenhydramine) or ranitidine isn’t needed for first-time users. Only consider it if you’ve had a previous reaction and need a faster infusion for clinical reasons. Even then, slowing the rate should come first.

What to Do If a Reaction Happens

If you start flushing or itching during an infusion:

- Stop the infusion immediately.

- Notify the nurse or doctor right away.

- Stay calm - this is not usually life-threatening.

- Most symptoms will fade within 30 minutes after stopping the drip.

If you’re having trouble breathing, swelling, or low blood pressure, treat it like a medical emergency. Oxygen, IV fluids, and sometimes epinephrine may be needed. But in most cases, just slowing or pausing the infusion is enough.

After the reaction, the medical team should document it correctly - as a vancomycin infusion reaction, not an allergy. They should also adjust future doses to prevent recurrence.

Other Drugs That Can Cause Similar Reactions

Vancomycin isn’t alone. Other antibiotics and drugs can trigger histamine release too:

- Amphotericin B - used for fungal infections - activates the complement system, leading to flushing and chills.

- Rifampin - used for TB - causes reactions through metabolites that bind to proteins, triggering immune responses.

- Ciprofloxacin - a fluoroquinolone - has been linked to flushing and hypotension in rare cases.

If you’ve had a reaction to one of these drugs, your provider should know. It doesn’t mean you’re allergic to all of them, but it does mean you need slower infusions and closer monitoring.

What’s the Bottom Line?

Vancomycin is a lifesaver. But it’s not a drug you can just push through a vein quickly. The reaction it can cause - once called “red man syndrome” - is preventable, predictable, and manageable. Slowing the infusion rate is the single most effective step. Using the right terminology protects patients from being wrongly labeled. And knowing the difference between a flushing reaction and a true allergy keeps you on the right treatment path.

If you’re prescribed vancomycin, ask: “How fast will this be given?” If the answer is “under an hour,” speak up. Your safety matters more than speed.

Is vancomycin infusion reaction the same as an allergy?

No. A vancomycin infusion reaction is not an allergy. It’s an anaphylactoid reaction caused by direct histamine release from cells, not by the immune system recognizing the drug as a threat. True allergies involve IgE antibodies and require prior exposure. You can have a flushing reaction the very first time you get vancomycin - which wouldn’t happen with a true allergy.

Can I get vancomycin again if I had a reaction before?

Yes, absolutely. Many people have reactions on their first dose but tolerate vancomycin fine on later doses - especially when it’s given slowly. The reaction often becomes less severe over time. As long as the infusion is slowed to 10 mg per minute or slower, most patients can safely receive vancomycin again. Never assume you’re allergic just because you flushed once.

Why do hospitals give vancomycin so slowly now?

Because research showed that infusing it faster than 10 mg per minute causes histamine release in most people. Slowing it down to 100 minutes or more for a 1-gram dose cuts the reaction rate from over 80% to less than 5%. It’s not about being cautious - it’s about science. Hospitals now follow guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America that require slow infusions as standard practice.

Do I need to take antihistamines before vancomycin?

Not if it’s your first time. Pre-medicating with diphenhydramine or ranitidine is only recommended for patients who’ve had a previous infusion reaction and need a faster infusion. For everyone else, slowing the drip is enough. Routine pre-medication doesn’t prevent reactions - it just adds extra drugs you don’t need.

Is vancomycin still safe to use if it causes flushing?

Yes. Vancomycin remains one of the most effective antibiotics for serious infections like MRSA. The flushing reaction is uncomfortable but rarely dangerous. With proper infusion speed, it’s avoidable. Avoiding vancomycin because of a flushed skin reaction could put you at greater risk from an untreated infection. The key is correct management - not avoidance.

Diana Stoyanova

January 9, 2026 AT 22:21Okay but can we talk about how wild it is that we used to call this 'red man syndrome'? Like, imagine if we still called asthma 'hysterical breathing' because it mostly happened to women in the 1800s? We wouldn't even joke about it. Yet somehow this stuck for decades. It's not just outdated-it's dehumanizing. And now we're finally fixing it? Good. Took long enough. 🙌

Micheal Murdoch

January 11, 2026 AT 00:35What's wilder is how many docs still don't know the difference between an infusion reaction and a true allergy. I had a nurse once tell me I was 'allergic to vancomycin' after I flushed during my first dose-so they switched me to something way broader and way more toxic. Took me six months to get back on the right med because no one would listen. Slowing the drip isn't 'being careful'-it's basic pharmacology. If your hospital still rushes it, ask why.

Patty Walters

January 11, 2026 AT 07:56just a quick heads up-dont forget that amphotericin b does the same thing. i saw a patient turn beet red during a 2-hour infusion and everyone panicked. turned out it was just the drug, not an allergy. slow drips save lives. also, no, you dont need benadryl every time. just chill and let it drip.

Jenci Spradlin

January 11, 2026 AT 11:35im a nurse and i can tell u-most units still rush vanco because they wanna ‘get it done.’ i had to fight my charge nurse to make her slow it down for a kid. she said ‘it’s just redness.’ i said ‘it’s histamine release, you idiot.’ she apologized later. the docs dont get it either. slow. it. down.

tali murah

January 12, 2026 AT 21:51Oh wow. Another woke medical term. Next they’ll rename ‘heart attack’ to ‘cardiac distress experience’ because it might offend someone who doesn’t believe in arteries. This isn’t progress-it’s performative language policing. The old term was descriptive. Now we’ve got 12 syllables for something that used to be called what it looked like. Also, I’ve seen patients flush. They didn’t die. Stop acting like this is the end of medicine.

Jeffrey Hu

January 14, 2026 AT 12:42Actually, the term 'red man syndrome' was coined in 1974 by Dr. K. M. W. Smith in *The New England Journal of Medicine*-not as a racial slur, but as a clinical descriptor. The shift to 'vancomycin infusion reaction' is scientifically accurate, yes, but the moral outrage over the old term is mostly performative. That said, the infusion rate guidelines are 100% correct. 10 mg/min is the magic number. Anything faster? You're asking for trouble. Also, ranitidine is obsolete. Use famotidine if you must pre-med.

Gregory Clayton

January 15, 2026 AT 05:33So now we can't even say 'red man' without being canceled? What's next? Calling a stroke a 'cerebrovascular emotional event'? This is why America's healthcare is broken. We're too busy policing words to fix actual problems. Vancomycin saves lives. If you get red and itchy, take a chill pill. Stop making everything about identity politics.

Heather Wilson

January 15, 2026 AT 05:42Let’s be honest-this whole ‘terminology shift’ is a distraction. The real issue is that hospitals still don’t have standardized protocols for vancomycin infusion. Some use pumps. Some use gravity. Some nurses don’t even know the 10 mg/min rule. Fix the system, not the name. Also, the fact that you’re even writing a 2000-word essay on this suggests you’re overcompensating for something.

Phil Kemling

January 15, 2026 AT 16:16It’s interesting how language reflects power. The term 'red man syndrome' was never about medicine-it was about who got to name things. Who gets to say what a patient looks like? Who gets to reduce suffering to a visual stereotype? Changing the name isn’t erasing history-it’s restoring dignity. And dignity, in medicine, isn’t optional. It’s the foundation.

Ashley Kronenwetter

January 16, 2026 AT 10:32While the terminology update is welcome, I must emphasize that clinical documentation must remain precise. The term 'vancomycin infusion reaction' is appropriate, but we must avoid conflating it with anaphylactoid responses that may have different underlying mechanisms. Furthermore, while slowing infusion rates is effective, we must also consider individual patient factors such as renal function, age, and concomitant medications. A one-size-fits-all approach remains insufficient.

Maggie Noe

January 18, 2026 AT 07:53Y’all are overthinking this 😅. It’s just a drug that makes you blush. If you get red, stop it, breathe, and wait. No one’s dying. No one’s being oppressed. Just slow the drip. And for the love of God, stop calling it ‘red man’-it’s 2025. We’ve got emojis for this now 🌈🫠🩸

Elisha Muwanga

January 20, 2026 AT 06:41So we’re spending millions retraining staff, updating EHRs, and rewriting guidelines to change a term that was never meant to be offensive? Meanwhile, real problems like antibiotic shortages, staffing crises, and hospital-acquired infections go ignored. This isn’t reform-it’s virtue signaling dressed in white coats. We need less semantics, more solutions. But hey, at least the patients are flushed.