Pharmacogenomics Drug Response Calculator

How Your Genes Affect Medications

This tool explains how genetic variations in key enzymes can impact how your body processes common medications. Select a drug below to see how your genetic profile might affect your response.

Select a medication to see details

Choose a medication from the dropdown above to see how genetic variations might affect your response.

Ever taken a medication that didn’t work-or made you feel worse? You’re not alone. For many people, the same dose of a drug that helps one person causes side effects in another. It’s not about being non-compliant or having a "weird" body. It’s about your genes.

Why Your Genes Decide How Drugs Work for You

Your body doesn’t treat every drug the same way. How quickly you break down a pill, how well it reaches your target, and whether it causes harm-all of that is influenced by tiny differences in your DNA. This is the core idea behind pharmacogenomics: using your genetic code to predict how you’ll respond to medications.Most drugs are processed by enzymes in your liver. The most important family of these enzymes? The cytochrome P450 system. Among them, CYP2D6 handles about 25% of all commonly prescribed drugs-antidepressants, beta-blockers, painkillers like codeine, and even some cancer drugs. But here’s the catch: people have different versions of the CYP2D6 gene. Some people are ultra-rapid metabolizers, meaning they break down the drug too fast-it never works. Others are poor metabolizers, so the drug builds up to toxic levels. One size does not fit all.

Take codeine, for example. It’s a prodrug-meaning your body has to convert it into morphine to relieve pain. That conversion relies entirely on CYP2D6. If you’re a poor metabolizer, you get almost no pain relief. If you’re an ultra-rapid metabolizer, you turn codeine into morphine so fast that you risk overdose, even at normal doses. That’s why some children died after tonsillectomies when given codeine for pain. The FDA now warns against using codeine in kids under 12 and in breastfeeding mothers.

The Big Players: Genes That Change Drug Outcomes

CYP2D6 isn’t the only gene that matters. Here are a few others with real-world impact:- CYP2C19: Affects clopidogrel (Plavix), a blood thinner used after heart attacks. About 30% of people have a variant that makes them poor metabolizers. They don’t convert the drug to its active form-and are at higher risk of another heart attack. Testing for this variant is now recommended before prescribing.

- TPMT: This enzyme breaks down thiopurine drugs like azathioprine, used for autoimmune diseases and leukemia. About 1 in 300 people have a genetic variant that makes them extremely sensitive. Without testing, they can develop life-threatening bone marrow suppression. Testing for TPMT is now standard before starting these drugs.

- UGT1A1: Affects irinotecan, a chemotherapy drug. People with a specific variant (UGT1A1*28) are at high risk of severe diarrhea and low white blood cell counts. Dosing is adjusted based on this result.

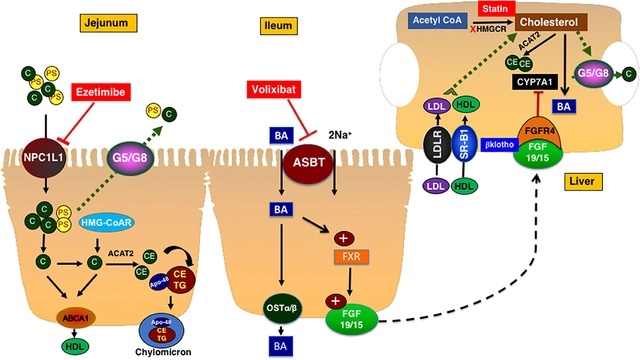

- SLCO1B1: Influences how your body absorbs statins like simvastatin. People with two copies of the risky variant have a 4.5 times higher chance of severe muscle damage. Doctors now avoid high doses in these patients.

These aren’t rare edge cases. Together, these four genes affect more than 100 commonly used drugs. And the number keeps growing. As of 2023, the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) has published 24 clear guidelines for how to adjust dosing based on genetic results.

What Does the Evidence Show?

It’s not just theory. Real studies show real benefits.A 2022 study in JAMA followed 1,838 people with depression. Half got treatment based on their CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 results. The other half got standard care. The genetically guided group had a 26.9% higher chance of remission and 29.7% fewer side effects. That’s not a small improvement-it’s life-changing for someone who’s tried three antidepressants without success.

For warfarin, the blood thinner used after strokes or clots, genetic testing cuts the time to reach the right dose by more than two days. It also reduces major bleeding in the first month by 31%. That’s a big deal-bleeding is the most dangerous side effect of this drug.

At Vanderbilt University, they’ve tested over 100,000 patients since 2012. The result? Half the time to find the right antidepressant. $1.9 million saved annually from avoided hospital visits. The VA has done similar testing for 100,000 veterans and saw 22% fewer hospitalizations.

These aren’t outliers. They’re proof that when you match the drug to the person’s genes, outcomes improve.

Why Isn’t Everyone Getting Tested?

If it works so well, why isn’t it routine?Cost is one barrier. A full pharmacogenomic panel costs $250-$500 in the U.S. Insurance doesn’t always cover it. In 2022, 18% of patients had their tests denied outright. Even when covered, prior authorization can take two weeks or more-too long if you’re in acute pain or at risk of a heart attack.

Then there’s the knowledge gap. Most doctors didn’t learn pharmacogenomics in med school. A 2023 survey found that 47% of clinicians struggle with interpreting results. Electronic health records rarely alert doctors when a patient’s genotype conflicts with a prescribed drug. Integration is slow.

And here’s the biggest problem: the data is biased. Over 90% of pharmacogenomic studies have been done on people of European descent. That means the guidelines we have may not apply to others. For example, the CYP2D6 variant that causes poor metabolism is rare in East Asian populations but common in Europeans. A test that works well for one group might miss the real issue in another. This isn’t just unfair-it’s dangerous.

Where Pharmacogenomics Works Best Right Now

Not every drug needs genetic testing. But for some, it’s a game-changer.- Psychiatry: 40-60% of people don’t respond to their first antidepressant. Genetic testing can cut trial-and-error time from months to days.

- Oncology: Testing for DPYD before giving 5-fluorouracil (a common chemo drug) prevents life-threatening toxicity in 0.2% of patients. That’s 1 in 500 people-enough to make testing standard.

- Cardiology: CYP2C19 testing before prescribing clopidogrel prevents heart attacks in poor metabolizers.

- Pain Management: Avoiding codeine in CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizers prevents overdose deaths.

- Autoimmune Diseases: TPMT testing before azathioprine prevents bone marrow failure.

For drugs like ibuprofen or metformin, genetic testing adds little value. They’re metabolized by multiple pathways, or have a wide safety margin. Testing isn’t needed there.

How to Get Started

If you’ve had bad reactions to meds, or if multiple drugs failed you, ask your doctor about pharmacogenomic testing.Here’s how to move forward:

- Ask your doctor if any of your current medications have known pharmacogenomic guidelines (CYP2D6, CYP2C19, TPMT, etc.).

- Request a test if you’re starting a high-risk drug like clopidogrel, thiopurines, or certain antidepressants.

- Check if your insurance covers it. Some Medicare Advantage and commercial plans do now.

- If you’ve used 23andMe or AncestryDNA, check if they include pharmacogenomics reports. They cover a few drugs (like codeine or statins), but not enough for full guidance.

- Bring your results to your pharmacist. They’re often the best person to interpret them and adjust your prescriptions.

Some hospitals now offer pre-emptive testing-getting your genes checked once, then storing the results for future use. That’s the future. One test, lifelong guidance.

The Future: Routine Testing by 2030

The World Health Organization now lists pharmacogenomics as a priority for global health systems. By 2030, Deloitte predicts 67% of healthcare systems will test everyone at age 18. The FDA approved its first next-generation PGx test in early 2023-one test, 27 genes, 350+ medications.It’s not magic. It’s science. And it’s finally moving out of labs and into clinics. The goal isn’t to replace doctors. It’s to give them better tools to make the right call the first time.

For patients, that means fewer side effects. Fewer hospital visits. Fewer failed treatments. And more confidence that the pill you take is the one your body was meant to handle.

What is pharmacogenomics?

Pharmacogenomics is the study of how your genes affect the way your body responds to medications. It helps doctors choose the right drug and dose for you based on your genetic makeup, reducing side effects and improving effectiveness.

Which genes are most important for drug metabolism?

The most clinically important genes are CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, TPMT, UGT1A1, and SLCO1B1. These affect how your body processes antidepressants, blood thinners, chemotherapy, painkillers, and statins. Variants in these genes can make drugs too strong, too weak, or toxic.

Is pharmacogenomic testing covered by insurance?

Coverage is growing but inconsistent. As of 2023, 87% of Medicare Advantage plans and 65% of commercial insurers cover at least one pharmacogenomic test-usually for high-risk drugs like clopidogrel or thiopurines. Many plans still require prior authorization, and some deny coverage outright. Always check with your insurer before testing.

Can I use 23andMe or AncestryDNA for pharmacogenomics?

Yes, but only partially. 23andMe reports on seven medications, including codeine, warfarin, and statins. However, it doesn’t test all relevant genes or variants, and it’s not a substitute for clinical testing. Use it as a starting point, not a final answer. Always confirm results with a healthcare provider.

Why doesn’t everyone get tested if it works so well?

Cost, lack of provider training, and slow integration into electronic health records are the main barriers. Also, most research has been done on people of European descent, so guidelines may not apply to everyone. Insurance coverage is improving, but many patients still face delays or denials.

What should I do if I’ve had bad reactions to medications?

Talk to your doctor or pharmacist about pharmacogenomic testing. Keep a list of drugs that didn’t work or caused side effects. Ask if any of them have known genetic links. If you’re starting a new high-risk medication like an antidepressant, blood thinner, or chemo drug, request testing before you begin. Your genes might explain why it didn’t work before-and help you find the right one next time.

Phil Thornton

November 29, 2025 AT 23:57Finally, someone explains why I felt like a zombie on SSRIs for six months. My body just didn't process them. No one ever told me it could be my genes.

Barbara McClelland

November 30, 2025 AT 06:56This is the kind of science that actually saves lives. Imagine if we tested everyone before prescribing antidepressants or painkillers. No more guessing games. No more suffering in silence. We’re not talking sci-fi here - this is practical, proven medicine. Let’s push for universal access.

Alexander Levin

November 30, 2025 AT 11:46So now Big Pharma wants to track our DNA to sell us more drugs? 🤔

Ady Young

November 30, 2025 AT 17:09I had a bad reaction to Plavix after my stent. Turned out I was a poor CYP2C19 metabolizer. My cardiologist had never heard of the test until I brought it up. Took three months to get it done. If this had been standard, I wouldn’t have nearly died. Everyone deserves this info before they start high-risk meds.

Also, the fact that most studies are on white people is wild. My cousin in India had a similar reaction to azathioprine - but the guidelines don’t even account for his variants. We’re leaving people behind.

Travis Freeman

December 1, 2025 AT 14:27Love how this ties into personalized care. I’m from a mixed background - South Asian and African American - and I’ve always felt like my body was an afterthought in medicine. This isn’t just about drugs. It’s about dignity. We’re not all the same, and pretending we are is what got us here.

Also, shoutout to pharmacists. They’re the unsung heroes who actually read these reports and fix your prescriptions before you end up in the ER.

Astro Service

December 1, 2025 AT 23:35Why do we need to test our DNA just to take a pill? Next they’ll be scanning our souls.

DENIS GOLD

December 3, 2025 AT 16:38Another woke science scam. They want you to think your genes are special so you’ll pay for tests. Meanwhile, the real problem is doctors who don’t listen. Just stop prescribing crap and listen to patients. That’s all we need.

gina rodriguez

December 5, 2025 AT 10:25I’ve been asking my doctor about this for years. She said it’s "too new." But the data’s been around since 2010. I’m glad someone finally put it all together. Maybe next time I’ll get the right med on the first try.

Sue Barnes

December 5, 2025 AT 18:29If you’re not getting tested, you’re gambling with your life. This isn’t optional anymore. It’s basic safety. Anyone who says it’s too expensive or inconvenient is putting profits over people. Stop normalizing suffering.

jobin joshua

December 6, 2025 AT 07:33My mom took warfarin for 8 years and bled every time they adjusted it. We found out she had a SLCO1B1 variant - now she’s on a different drug and fine. This saved her life. 🙏