Medication & Fertility Impact Calculator

Impact Analysis Results

Select medications and your fertility goal, then click "Analyze Medication Impact" to see how they may affect ovulation and fertility.

Key Points

- Prescription meds can either suppress or boost ovulation depending on their class.

- Common culprits that lower fertility include hormonal contraceptives, certain antidepressants, and some anti‑epileptic drugs.

- Drugs like clomiphene citrate and letrozole are intentionally used to induce ovulation.

- Stopping a fertility‑impacting medication doesn’t always restore ovulation instantly; the timeline varies.

- Open conversations with your clinician are essential for balancing treatment needs and reproductive goals.

When it comes to trying to conceive, the role of medications affecting ovulation and fertility is often misunderstood. Some people assume any drug will harm their chances, while others think only birth‑control pills matter. The truth sits somewhere in the middle, and understanding the science helps you make smarter choices.

Understanding Ovulation and Fertility

Ovulation is the monthly release of an egg from the ovary, driven by a cascade of hormones - mainly luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle‑stimulating hormone (FSH). When ovulation occurs, the window for fertilisation opens, and the likelihood of pregnancy spikes.

Fertility refers to the ability to achieve a successful pregnancy. It hinges on regular ovulation, healthy egg quality, a receptive uterine lining, and supportive hormonal balance. Any medication that tweaks these signals can swing the odds.

How Medications Can Disrupt Ovulation

Most drugs affect fertility indirectly by altering hormone levels, impacting blood flow, or changing the uterine environment.

Oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) - the classic example - contain synthetic estrogen and progestin. They suppress the hypothalamic‑pituitary‑ovarian axis, preventing the LH surge and thus stopping ovulation. While effective for birth control, they also pause natural cycles. Recovery of ovulation typically resumes within 1‑2 months after stopping, but for some women it may take up to six cycles.

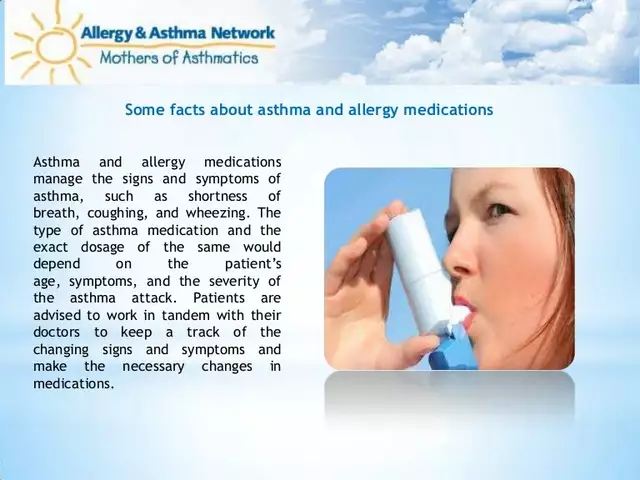

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a popular class of antidepressants, can raise prolactin levels. Elevated prolactin can inhibit GnRH release, blunting the LH surge and leading to anovulatory cycles in up to 15% of users.

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) such as valproate and carbamazepine interfere with folate metabolism and can cause polycystic ovarian morphology, which often translates to irregular ovulation.

Non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen, when taken in high doses for prolonged periods, may block prostaglandin synthesis required for follicular rupture, transiently delaying ovulation.

For women with thyroid disorders, inadequate dosing of thyroid medication (levothyroxine) can keep TSH levels outside the optimal range, resulting in irregular cycles.

Prescription Drugs That May Reduce Fertility

Below is a quick snapshot of meds most frequently linked to lowered conception rates:

| Medication Class | Typical Ovulation Effect | Mechanism | Fertility Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Combined oral contraceptives | Suppression | Inhibit LH surge via estrogen & progestin | Cycle resumes 1‑6 months after discontinuation |

| SSRIs (e.g., fluoxetine) | Partial suppression | Elevate prolactin, dampen GnRH | Switching to non‑serotonergic antidepressant may help |

| Valproate (AED) | Irregular or absent ovulation | Disrupts folate metabolism, induces PCOS‑like changes | Consider alternative AEDs pre‑conception |

| High‑dose NSAIDs | Delay | Blocks prostaglandin‑mediated follicle rupture | Limit use to short courses |

| Levothyroxine (under‑dose) | Irregular | Thyroid hormone imbalance disrupts cycle timing | Maintain TSH 0.5‑2.5mIU/L for optimal fertility |

| Chemotherapy agents | Temporary or permanent suppression | Gonadotoxic damage to ovarian reserve | Fertility preservation (egg/embryo freezing) advised |

Drugs That Can Actively Promote Ovulation

When a woman experiences anovulation, clinicians often turn to medications designed to jump‑start the process.

Clomiphene citrate is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM). By blocking estrogen feedback at the hypothalamus, it forces the pituitary to release more FSH and LH, encouraging follicle development. Typical success rates hover around 70% for first‑line cycles.

Letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, reduces estrogen synthesis, similarly lifting the hypothalamic brake. Recent studies suggest letrozole may yield higher live‑birth rates than clomiphene, especially in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Metformin, primarily a diabetes medication, improves insulin sensitivity and can restore regular ovulation in up to 30% of women with PCOS, often used alongside clomiphene or letrozole.

Managing Fertility While on Necessary Medication

Sometimes you can’t simply stop a drug - chronic conditions like epilepsy or depression need continuous treatment. Here’s a practical framework:

- Assess necessity: Talk with your specialist about whether the current dose is the lowest effective one.

- Explore alternatives: For depression, consider bupropion, which has a lower prolactin effect. For seizures, lamotrigine is less linked to ovarian dysfunction.

- Timing is key: If a drug can be paused for a short window (e.g., NSAIDs), schedule a two‑week break around your predicted ovulation.

- Supplement strategically: Folate (400‑800µg) and vitamin D support ovarian health, especially when on AEDs.

- Track cycles: Use basal body temperature, LH kits, or fertility apps to pinpoint ovulation despite medication interference.

In many cases, a collaborative approach between your OB‑GYN and prescribing physician yields a plan that respects both health and reproductive goals.

How Long Does It Take for Ovulation to Return?

Recovery timelines differ by drug class:

- Oral contraceptives: Most women ovulate within one month; a minority need up to six cycles.

- SSRIs: If switched to a non‑serotonergic agent, prolactin usually normalises in 4‑6 weeks.

- Valproate: Ovulation may improve within three months after switching, but ovarian reserve may be permanently reduced.

- Chemotherapy: Recovery depends on age and drug type; some women regain function, others require assisted reproductive technologies.

Patience is vital. Tracking your menstrual signs during the transition period gives concrete data on when your body resumes its natural rhythm.

Talking to Your Healthcare Provider

Bring a concise list to appointments:

- All current prescriptions (including dose and frequency).

- Any over‑the‑counter or herbal supplements.

- Specific fertility timeline - when you hope to conceive.

Ask targeted questions such as:

- "Is there a safer alternative for my condition that won’t affect ovulation?"

- "If I stay on this medication, what monitoring should we do?"

- "Should I consider fertility preservation before changing treatment?"

Clear communication reduces uncertainty and helps you avoid unnecessary delays.

Quick Reference Table

| Medication | Effect on Ovulation | Suggested Action |

|---|---|---|

| Combined OCPs | Suppressed | Discontinue 1‑2 months before trying to conceive |

| Fluoxetine (SSRI) | Partial suppression | Discuss switch to bupropion or dose reduction |

| Valproate | Irregular/absent | Consider alternative AED; if not possible, monitor closely |

| Clomiphene citrate | Stimulates | Prescribed by fertility specialist for anovulatory cycles |

| Letrozole | Stimulates | Often first‑line for PCOS‑related anovulation |

| Metformin | Improves regularity | Adjunct for insulin‑resistant PCOS patients |

Understanding how each drug interacts with the reproductive system empowers you to make choices that align with both health and family‑building goals. Remember, the relationship between medications and fertility isn’t black‑and‑white - it’s a spectrum that can be navigated with the right information and professional guidance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can birth‑control pills cause long‑term infertility?

No. OCPs temporarily suppress ovulation, but ovarian reserve remains unchanged. Most women regain normal cycles within a few months after stopping the pill. Persistent irregularity beyond six months warrants a medical check‑up.

Is it safe to stay on antidepressants while trying to get pregnant?

It depends on the specific drug. SSRIs like fluoxetine may raise prolactin and slightly reduce fertility, but the risk of untreated depression often outweighs the modest impact on conception. Discuss alternatives or dose adjustments with your psychiatrist.

How does valproate affect a woman’s chance of pregnancy?

Valproate can cause polycystic‑ovary‑like changes, leading to irregular or absent ovulation and a reduced ovarian reserve. Switching to levetiracetam or lamotrigine before conception is usually recommended.

Do NSAIDs really stop ovulation?

High‑dose or prolonged NSAID use can delay the follicular rupture needed for ovulation because prostaglandins help the egg break free. Short‑term use for pain relief typically doesn’t affect fertility.

Can I use fertility‑boosting drugs if I’m already on metformin?

Yes. Metformin often complements ovulation‑inducing agents like clomiphene or letrozole, especially in women with insulin‑resistant PCOS. The combination can improve response rates and lower the need for high‑dose fertility drugs.

Clara Walker

October 1, 2025 AT 20:34The pharmaceutical giants are deliberately hiding the long‑term fallout on women’s fertility.

Jana Winter

October 3, 2025 AT 02:06While the article attempts to be comprehensive, it contains numerous grammatical errors; for example, the phrase “medication & fertility impact calculator” should capitalize “Calculator,” and the sentence “Recovery timelines differ by drug class” lacks a terminating period. Moreover, the inconsistent use of hyphens versus en dashes creates visual clutter. A polished piece would adhere to the Chicago Manual of Style for serial commas and maintain parallel structure throughout.

Linda Lavender

October 4, 2025 AT 08:40Reading through the exhaustive list of medications, one is struck by the sheer variety of mechanisms by which drugs interfere with the hypothalamic‑pituitary‑ovarian axis, a delicate hormonal orchestra that governs monthly ovulation. Combined oral contraceptives, for instance, flood the system with synthetic estrogen and progestin, delivering a potent negative feedback loop that suppresses the LH surge and thereby halts follicular rupture; this effect is intentional but it also illustrates how easily exogenous hormones can commandeer endogenous rhythms. SSRIs such as fluoxetine, though primarily targeting serotonergic pathways, have a secondary impact on prolactin secretion, and elevated prolactin is notorious for dampening GnRH pulses, leading to anovulatory cycles in a notable minority of users. Anticonvulsants like valproate perturb folate metabolism and can induce a polycystic‑ovary‑like phenotype, which not only disrupts ovulation but may also diminish ovarian reserve over the long term. High‑dose NSAIDs, when taken continuously, inhibit prostaglandin synthesis that is essential for follicular rupture, effectively delaying the oocyte’s release. Sub‑therapeutic levothyroxine dosing skews thyroid hormone homeostasis, pushing TSH outside the optimal fertility window and resulting in irregular cycles. On the other side of the spectrum, agents such as clomiphene citrate and letrozole are deliberately employed to stimulate ovulation by antagonizing estrogen feedback and reducing estrogen synthesis, respectively, thereby freeing the pituitary to increase FSH and LH output. Metformin’s role in enhancing insulin sensitivity provides an ancillary benefit for women with PCOS, restoring a more regular ovulatory pattern in many cases. The timelines for recovery after discontinuation vary wildly; while most women resume ovulation within one to two months after stopping combined oral contraceptives, those who have been on valproate may require several months, and some may never fully recover their prior ovarian reserve. This variability underscores the importance of individualized counselling and careful monitoring when planning conception. Moreover, the psychological burden of navigating medication adjustments cannot be understated; patients often feel caught between managing chronic illness and preserving fertility. Collaborative care involving obstetricians, psychiatrists, neurologists, and primary care physicians is essential to balance therapeutic efficacy with reproductive goals. In practice, a stepwise approach-optimizing the lowest effective dose, exploring alternative agents, and timing medication pauses around the predicted fertile window-can mitigate many of the adverse effects described. Nonetheless, for certain conditions such as refractory epilepsy or severe depression, complete cessation may not be feasible, and patients must weigh the risks and benefits with their healthcare team. Finally, the article rightly emphasizes the value of tracking ovulatory signs, whether through basal body temperature, LH surge kits, or modern fertility apps, as these data provide objective feedback on how the body responds to medication changes. In summary, a nuanced understanding of each drug’s mechanism, coupled with vigilant clinical oversight, empowers women to make informed decisions about their reproductive health.

Jay Ram

October 5, 2025 AT 16:36Hey, if you’re feeling overwhelmed by the med list, just remember you’ve got tools-cycle trackers, supportive docs, and a community that’s got your back.

Elizabeth Nicole

October 7, 2025 AT 00:33Exactly! Start by noting any irregularities for a few months, then bring that log to your OB‑GYN; they can pinpoint whether a medication tweak is needed or if you’re simply riding a natural variation.

Dany Devos

October 8, 2025 AT 08:30The author fails to cite primary literature for the claims regarding NSAID‑induced ovulatory delay, rendering the statement speculative rather than evidence‑based. A rigorous review would reference at least two randomized controlled trials. Additionally, the recommendation to “maintain TSH 0.5‑2.5 mIU/L” is overly precise without acknowledging individual target ranges.

Sam Matache

October 9, 2025 AT 16:26Wow, another crusade against “big pharma”-as if the entire medical establishment is a secret cabal plotting to sabotage motherhood. The science is clear, the data are published, and the doctors are doing their jobs, not conspiring.

Hardy D6000

October 11, 2025 AT 00:23Actually, it’s precisely the lack of transparency that fuels distrust; you can’t ignore the fact that many drug trials exclude women of childbearing age, leaving us with incomplete safety profiles. Moreover, the “doctors are doing their jobs” narrative glosses over systemic biases that prioritize profit over patient autonomy.

Amelia Liani

October 12, 2025 AT 08:20I hear your concerns, and it’s painful to see those gaps in research. While we await broader inclusion, sharing personal experiences and advocating for more inclusive trials can gradually shift the paradigm toward greater accountability.

shikha chandel

October 13, 2025 AT 16:16Selective reporting in clinical studies is a well‑known issue that warrants scrutiny.

Mary Ellen Grace

October 15, 2025 AT 00:13Totally agree-let’s keep the conversation friendly and push for more openness in research!