Most people assume that before a generic drug hits the shelf, it must be tested on people. That’s not always true. The FDA lets drugmakers skip human trials altogether - if the science backs it up. This isn’t a loophole. It’s a carefully designed shortcut called a bioequivalence waiver, or biowaiver. And for certain generic drugs, it’s the fastest, cheapest, and most reliable path to market.

What Exactly Is a Bioequivalence Waiver?

A bioequivalence waiver is when the FDA says: “You don’t need to give this drug to volunteers to prove it works the same as the brand-name version.” Instead, you prove it using a test tube. Specifically, you show that your generic dissolves in lab solutions at the same rate and to the same extent as the original drug. If the dissolution profiles match perfectly under strict conditions, the FDA accepts that the drug will behave the same inside the body - without ever touching a human subject. This isn’t theoretical. In 2022, nearly 18% of all generic drug applications (ANDAs) for solid oral tablets and capsules used a biowaiver. That’s up from 12% just five years earlier. The reason? It saves companies $250,000 to $500,000 per product and cuts approval time by 8 to 10 months. For small manufacturers, that’s the difference between launching a product or shelving it.Which Drugs Qualify?

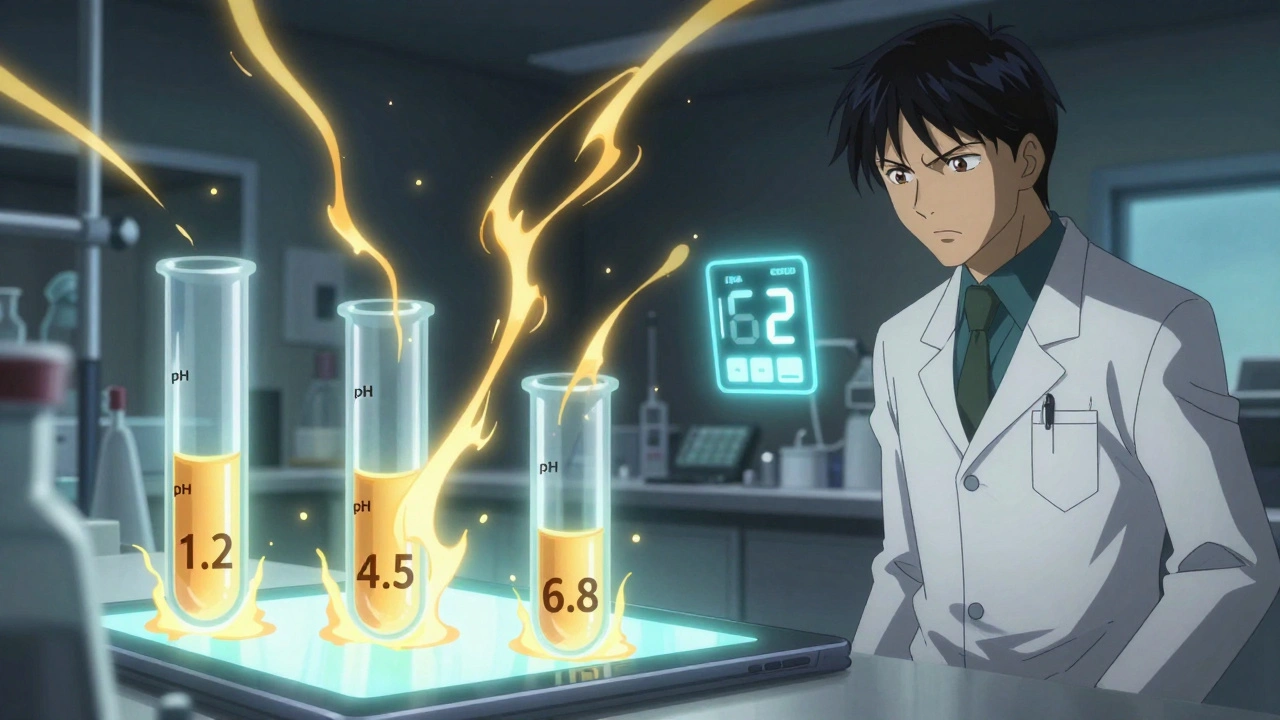

Not every drug gets a free pass. The FDA only allows biowaivers for immediate-release (IR) solid oral dosage forms - think plain tablets or capsules you swallow. No liquids, no patches, no extended-release pills. And even among those, only certain types qualify based on the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS). The BCS groups drugs into four classes based on two things: how well they dissolve in the gut (solubility) and how easily they cross into the bloodstream (permeability). Only two classes are eligible for biowaivers:- BCS Class I: High solubility, high permeability. These are the easiest. Examples include metformin, atorvastatin, and ciprofloxacin. For these, you need to show that your generic dissolves at least 85% within 30 minutes in three different pH buffers (pH 1.2, 4.5, and 6.8), and that the dissolution profile matches the brand-name drug with an f2 similarity factor of 50 or higher.

- BCS Class III: High solubility, low permeability. These are trickier. Drugs like aminoglycoside antibiotics or aliskiren fall here. For these, you need to match the brand not just in dissolution, but also in excipients - the inactive ingredients like fillers and binders. Even a slight change in lactose or magnesium stearate can trigger a rejection.

How Do You Prove Dissolution Is Good Enough?

It’s not enough to say your tablet dissolves fast. You have to prove it in a way that the FDA can’t ignore. The process is rigid:- Use at least 12 units of your product and the brand-name reference.

- Test dissolution in three buffers: stomach-like (pH 1.2), small intestine-like (pH 4.5), and intestinal (pH 6.8).

- Sample at 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, and 60 minutes.

- Calculate the f2 similarity factor - a statistical measure comparing your dissolution curve to the reference. If it’s 50 or higher, you pass.

- Prove the method is discriminatory - meaning it can tell the difference between a good and bad formulation.

Why Does This Even Exist?

The FDA isn’t cutting corners. It’s cutting waste. For drugs that dissolve and absorb predictably - like Class I drugs - human studies are redundant. Blood samples from volunteers don’t tell you anything new. The drug’s behavior is controlled by dissolution, not absorption. If the tablet breaks down the same way, it will be absorbed the same way. That’s been proven over and over. A 2020 study in the AAPS Journal found that BCS-based biowaivers matched in vivo outcomes with over 95% accuracy for Class I drugs. That’s better than most clinical trials. The FDA’s own data from 2012 to 2016 showed that 78% of well-documented biowaiver requests were approved. That’s not luck. That’s science. The savings aren’t just financial. Every biowaiver means one fewer healthy volunteer exposed to a drug they don’t need. It also means faster access to affordable medicines. IQVIA estimates that biowaivers have accelerated generic drug approvals by an average of 7.3 months per product - translating to over $1.2 billion in earlier market access each year.Where the System Gets Messy

Despite its success, the biowaiver system isn’t perfect. Some companies report inconsistent decisions across FDA review divisions. One team approves a Class III waiver based on excipient matching; another rejects the same application because they want “more data.” A 2022 PhRMA survey found that 42% of companies felt the criteria were applied unevenly. Class III drugs are especially problematic. Even when manufacturers meet every technical requirement, approval rates are low. One regulatory specialist reported three out of five Class III biowaiver submissions still required human studies - despite following the guidance exactly. And then there’s the big blind spot: modified-release products. No biowaiver exists for extended-release tablets, delayed-release capsules, or any formulation designed to release the drug slowly. The FDA says the science isn’t there yet. But that’s changing. A 2023 pilot program is testing whether certain extended-release drugs can qualify under new models. If successful, this could open the door for hundreds of additional generic drugs.

What’s Next?

The FDA’s 2023-2027 strategic plan aims to expand biowaiver eligibility by 25%. That means more Class III drugs, possibly even some narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs like levothyroxine or warfarin - if new models prove they can be trusted. The agency is also investing $15 million annually through GDUFA to improve dissolution testing methods and build better in vitro-in vivo correlations (IVIVC). That’s not just paperwork. It’s building the tools to make biowaivers more accurate, more reliable, and available to more drugs. For generic manufacturers, the message is clear: if your drug fits the BCS Class I profile, invest in dissolution testing early. Don’t wait until you’re ready to file. Start method development in Phase 1 of formulation. Use the FDA’s Pre-ANDA program for feedback before submitting. Companies that do this have a 22% higher approval rate.Bottom Line

Bioequivalence waivers aren’t a shortcut for lazy companies. They’re a smart, science-driven policy that saves money, speeds up access to generics, and reduces unnecessary human testing. The FDA doesn’t waive in vivo studies because it’s lazy - it does it because it knows, for certain drugs, the test tube is more reliable than the bloodstream. If you’re developing a generic tablet that dissolves quickly and is absorbed completely, a biowaiver could be your fastest route to market. But if you’re cutting corners on dissolution testing, you’re not saving time - you’re setting yourself up for rejection.Can any generic drug get a bioequivalence waiver?

No. Only immediate-release solid oral dosage forms that meet specific BCS criteria qualify. BCS Class I drugs (high solubility, high permeability) are the most common. Some BCS Class III drugs (high solubility, low permeability) may qualify if excipients match exactly. Modified-release, liquid, injectable, and topical products are not eligible.

How much does a bioequivalence waiver save compared to an in vivo study?

A single in vivo bioequivalence study costs between $250,000 and $500,000 and takes 6 to 12 months to complete. A biowaiver, by contrast, typically costs under $50,000 and takes 3 to 6 months from start to submission - saving companies hundreds of thousands of dollars and accelerating approval by 8 to 10 months per product.

What is the f2 similarity factor and why does it matter?

The f2 similarity factor is a statistical measure used to compare dissolution profiles between the generic and brand-name drug. An f2 value of 50 or higher indicates the two profiles are similar enough to predict bioequivalence. If the value is below 50, the FDA will likely require an in vivo study. It’s the single most important number in a biowaiver application.

Why are Class III drugs harder to get approved for biowaivers?

Class III drugs are poorly permeable, so their absorption depends on how they’re formulated - not just how fast they dissolve. The FDA requires exact matching of excipients (inactive ingredients) and proof that absorption isn’t affected by where in the gut the drug dissolves. Even small differences in binders or coatings can trigger rejection, making approval much more difficult than for Class I drugs.

Do biowaivers apply to narrow therapeutic index drugs?

Generally, no. Drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, or phenytoin have narrow therapeutic windows, meaning small differences in absorption can cause harm. The FDA typically requires in vivo studies for these. However, exceptions exist - for example, certain antiepileptic drugs have been approved via biowaiver under specific, detailed guidance. New pilot programs are exploring whether this can be expanded.

David Brooks

December 8, 2025 AT 02:49This is one of those rare cases where the FDA actually gets it right. No need to stick needles in healthy people when a test tube tells you everything you need to know. Class I drugs? Perfect. The dissolution profile is basically the drug’s DNA. If it matches, it’s the same molecule doing the same job. It’s not cutting corners-it’s cutting the noise.

Ashley Farmer

December 9, 2025 AT 05:38Thank you for explaining this so clearly. I’ve always wondered why some generics are approved so fast-now I know it’s not because they’re lazy, but because the science is solid. For people who can’t afford brand-name meds, this is life-changing.

Nicholas Heer

December 9, 2025 AT 15:00They’re letting Big Pharma skip human trials? 😏 Classic. Next they’ll say ‘trust the algorithm’ for cancer drugs. This is how they bury the truth-‘bioequivalence’ my ass. The real reason? Profit. They don’t want to pay for trials, so they slap a fancy label on it and call it ‘science.’ You think they’d let this fly for insulin? Nah. Only for the cheap stuff.

Olivia Hand

December 10, 2025 AT 06:58Wait-so if a Class III drug’s excipients change even slightly, it gets rejected? That’s wild. So it’s not just about the active ingredient anymore-it’s about the filler in the pill. Who decides what’s ‘safe’ in the filler? Is magnesium stearate really that finicky? I feel like I’m reading a pharmaceutical cookbook now.

Ted Rosenwasser

December 10, 2025 AT 11:03Let me break this down for the laypeople who think ‘generic’ means ‘inferior.’ This isn’t some backroom loophole-it’s a validation of pharmacokinetic predictability. The BCS framework is rooted in physicochemical principles that have been peer-reviewed for decades. If your tablet dissolves identically under standardized conditions, the bioavailability is functionally equivalent. Period. Human trials for Class I drugs are statistically redundant and ethically questionable when you consider the cost-benefit ratio. The FDA isn’t lazy; they’re optimized.

And before you say ‘but what about individual variation?’-that’s why we have post-marketing surveillance. The system works because it’s probabilistic, not deterministic. You don’t need to test every person to know the population curve.

Also, f2 > 50 isn’t arbitrary-it’s derived from the 90% confidence interval of the mean difference. If you don’t understand the math behind it, you’re not qualified to critique it. This isn’t a blog post-it’s regulatory science.

And yes, Class III is harder. Why? Because permeability is the bottleneck. Dissolution is easy to control. Absorption isn’t. That’s why excipient matching matters. Lactose isn’t just ‘filler’-it affects dissolution kinetics in the GI tract. You think that’s trivial? Try swallowing a pill with a different binder and see how fast your gut reacts.

And don’t get me started on the myth that ‘all generics are the same.’ They’re not. Some are garbage. That’s why the FDA requires dissolution testing. It’s not a favor-it’s a filter.

Also, the $500K savings? That’s real. That’s why small generic manufacturers survive. Without biowaivers, half the affordable meds on your shelf wouldn’t exist. You want cheaper insulin? This is how you get it.

And yes, the FDA is expanding this. They’re not dumb. They’re using machine learning to model IVIVC. The future is predictive pharmacokinetics. You’re still stuck in the 1980s.

Helen Maples

December 10, 2025 AT 17:33Someone needs to tell the FDA that ‘f2 similarity factor’ isn’t a magic number. It’s a guideline. I’ve seen applications rejected for f2=49.8 and approved for f2=49.2 because the reviewer had a bad day. This isn’t science-it’s a lottery with lab coats.

Kyle Flores

December 10, 2025 AT 21:40Hey, I work in a compounding pharmacy and I’ve seen how inconsistent these waivers can be. One lab gets it approved, another says ‘we need more data.’ It’s frustrating. But I get it-better safe than sorry. Still, if the science says it’s fine, why the back-and-forth? Maybe we need a national standard for dissolution testing.

Nancy Carlsen

December 11, 2025 AT 04:13This is so cool. I love that science is being used to make medicine more accessible. 🌍✨ Imagine if we applied this logic to other areas-like vaccines or diagnostics. Less testing on people, more on machines. It’s not cold-it’s compassionate.

Sadie Nastor

December 12, 2025 AT 06:07wait so if my pill dissolves in 29 mins instead of 30 its rejected? 😅 i feel bad for the chemists who spend months on this

Louis Llaine

December 13, 2025 AT 11:54So the FDA lets companies skip human trials… but only if they can prove their pill dissolves like the expensive one. Cool. So what’s the difference between this and saying ‘it looks the same, so it works’? 😏

Stacy here

December 15, 2025 AT 00:07They’re not letting you skip trials-they’re letting you skip the truth. The body isn’t a test tube. The gut isn’t a beaker. The FDA knows this. But they’re too cozy with Big Pharma to admit it. This isn’t science-it’s corporate convenience dressed up as innovation. They’re betting that no one will notice when a generic fails in the wild. And when it does? They’ll blame the patient. ‘Oh, you didn’t take it right.’ Meanwhile, the $500K saved is lining someone’s bonus.

Jennifer Anderson

December 15, 2025 AT 14:52just wanna say thank you for writing this. i didn’t know any of this and now i feel smarter. also the part about class iii drugs and excipients? mind blown. 🤯